By Mark David (mark-david.com)

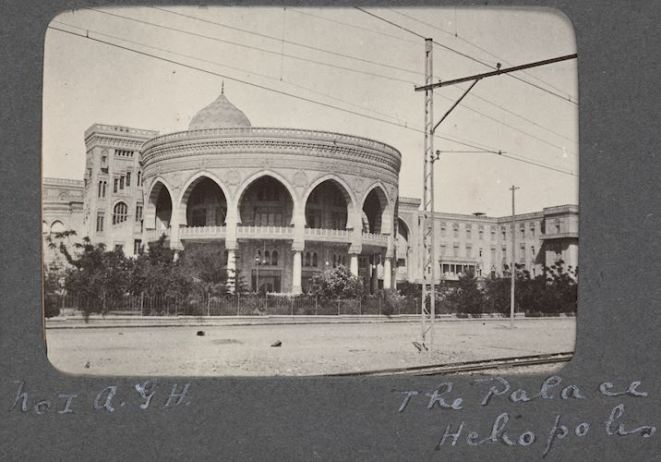

The grand Heliopolis Palace Hotel was built in 1910, refuted to be the most luxurious hotel of the time in Africa and the Middle East. With its architectural emminence the Heliopolis Palace Hotel became a travel destination for many, including foreign royals and international business tycoons. The hotel was designed by Belgian architect Ernest Jaspar, using the services of architect Alexandre Marcel to design the central dome using the local Heliopolis style of architecture, a synthesis of Persian, Moorish Revival, Islamic, and European Neoclassical architecture that became known as the Heliopolis style.

In its time, the luxurious Heliopolis Palace Hotel exceeded in service and elegance such great Cairo hotels as Shephard's (no longer existing) and the Continental (existing but not operational) both overlooking the Azbakia gardens and Opera square, as well as Mena House Hotel at the foot of the pyramids and the Semiramis Hotel (non-existent but replaced by a new tower and management).

The hotel was built by the contracting firms Leon Rolin & Co. and Padova, Dentamaro & Ferro, the two largest civil contractors in Egypt then. Siemens & Schuepert of Berlin fitted the hotel’s web of electric cables and installations. The utilities were to the most modern standards of their day. The hotel operations were under French administered management.

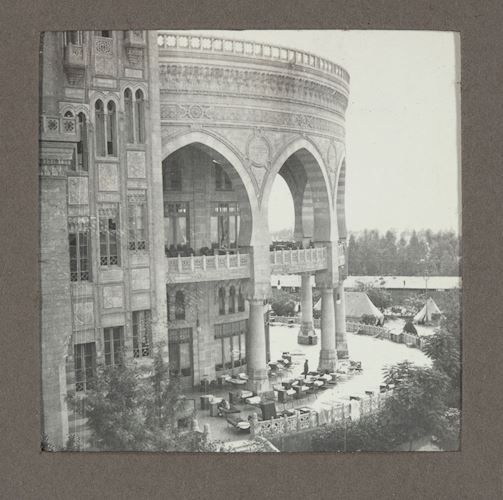

The Heliopolis architectural style, responsible for many wonderful original buildings in Heliopolis, was exceptionally expressed in the Heliopolis Palace Hotel’s exterior and interior design. The hotel had 400 rooms, including 55 private apartments. Beyond the Moorish Revival reception hall two public rooms were lavishly decorated. Beyond those was the Central Hall, the primary public dining space with a classic symmetrical and elegant beauty.

Description

The Central Hall’s dome, awe inspiring to guests, measured 55 metres (180 ft) from floor to ceiling. The 589 square metres (6,340 sq ft) hall’s architectural interior was designed by Alexander Marcel of the French Institute, and decorated by Georges-Louis Claude. Twenty-two Italian marble columns circled the parquet floor up to the elaborate ceilings. The hall was carpeted with fine Persian carpets and had large mirrored wall panels and a substantial marble fireplace. To one side of the Central Hal was the Grillroom seating 150 guests, and to the other was the billiards hall, with two full-sized British Thurston billiard tables and a ‘priceless’ French one. The private banquet halls were quite large and elaborate.

One of the main features of the original design is a half-round building feature in the middle of the rear elevation on the same axis as the entrance portal and the dome. It once functioned as a golden age banquet hall but was originally intended to be a casino to entertain the citizens of the remote Heliopolis “oasis.”

The Interior

Photos of this banquet hall’s interior are rare. The mahogany furniture was ordered from Maple’s of London. Damascus-made ‘East Orient style’ lamps, lanterns, and chandeliers hung throughout, suspended like stalactite pendants. The upper gallery contained oak-paneled reading and card rooms furnished by Krieger of Paris. The basement and staff areas were so large that a narrow gauge railway was installed running the length of the hotel, passing by offices, kitchens, pantries, refrigerators, storerooms and the staff mess. Notable is the replacement of the traditional original parquet with marble in an arabesque pattern.

Echoes of the War: A Base Hospital

The First Australian General Hospital is installed in the magnificent premises of the Heliopolis Palace Hotel. The building is said to be the most gorgeous hotel building in the whole world, but to day it is filled with the manifold activities of a great general hospital. The figures themselves are large, accommodation for 1,000 sick, but when you pass along corridor after corridor, every door opening on the neat white beds in every room, when you find the grand dining-hall converted into a great convalescent ward with 100 beds, then you begin to understand something of this great institution, filled alas, to-day with the flotsam of youth being prepared for war. For there are no wounded in our 600 sick, only the toll being paid to pneumonia, rheumatism, influenza, and the obscure diseases of this Eastern land. No, it is not a hotel to-day, for grey-robed nursing sisters from Australia move quietly around, cheerfully doing heroic service, and khaki-clad orderlies carrying stretchers or filling their multitudinous duties, pass along the halls and passages. Truly motors constantly come and go, at the front entrance, but they are painted white or grey with the big red cross on sides and top, and their passengers more frequently than not are carried up the marble steps into the spacious entrance hall. And sometimes, alas, the slow march of troops is heard, and the tramp of horses’ feet, the grinding of the wheels of the gun-carriage, for a party of men have come to take away, and pay last honours to the comrade who has died. Within these walls great fights have been, are being fought, medical skill and attention beyond all praise, nursing that fails not, day or night, against the disease that would destroy. Great victories have been won. A haggard man will tell you that he has lost a month of memory. A few months will fill again the wasted cheeks, and build again the muscular limbs, but that lost month of his was spent by nurses and medical officer in an apparently hopeless war against pneumonia and typhoid combined. Again and again defeat seemed inevitable, but the Australian nurses nursed to the last, and victory was snatched, out of apparent defeat. Peace hath victories more wonderful than war. But there are sad things here — too sad for words. Let all who in the Homeland are mourning their dead lying in Egyptian graves know this — that nothing can surpass the tenderness and care with which our Australian women ease the last moments of our boys who die here.

1915 ‘Echoes of the War.’, Spectator and Methodist Chronicle (Melbourne, Vic. : 1914 – 1918), 18 June, p. 882, viewed 13 September, 2014, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article154169500

The unit left Australia as a General Hospital of 520 beds. In Egypt, during 1916, the establishment was increased to 750 beds and later, in France, in 1916, it was increased to 1040 beds.The staff and equipment embarked on board the S. S. “Kyarra” along with four other Medical Units of the A. I. F. viz : N° 2 Australian General Hospital, N°s 1 & 2 Aust. Stationary Hospitals and N° 1 Australian Casualty Clearing Station, and sailed for Egypt on 2ist November 1914.Arriving in Egypt on January 14th 1915, the 1st A. G. H. wns accomodated in a building and tents at Heliopolis, a suburb of Cairo. The building was very large and palatial, and is well known as the Heliopolis Palace Hotel. On January 24th 1915 the Hospital was opened for the reception of patients. The patients received consisted of all ranks of the A.I.F., and all classes of cases were treated. After a short period, and owing to circumstances, the hospital took over other additional premises for the treatment of different classes of cases. Amongst such were Aerodrome; The Luna Park; The Atelier; The Sporting Club buildings and grounds at Heliopolis, and The Artillery Barracks at Abbassia Depots, and they were attached to and within the command of the 1st A. G. H. Subsequently, however, all of these Auxiliaries, with the exception of the Aerodrome which was closed in April 1915, were made into separate A. A. M. C., A. I. F. units, each with its own personnel and equipment. They became respectively the N° 1, N° 2, N° 3 and N° 4. Australian Auxiliary Hospitals in Egypt, each of which has a history of its own.The 1st A.G.H. had a most useful career from fourteen to fifteen months in the land of the Pharoahs, having served there from January 1915 to March 1916. During that period the hospital attended to its full share of patients from A.I.F. troops serving in Egypt, also its share of. Australian sick and wounded soldiers who had served in the Gallipoli Expedition in 1915.In March 1916, following upon the decision that the A.I.F. should serve in France, the various A.A.M.C. units were ordered to close and pack up, their patients being transferred to the Auxiliary and other Hospitals.The 1st A.G.H., after a hurried departure from Heliopolis, with personnel and equipment for an establishment of 750 beds, embarked at Alexandria on 29th march 1916 upon H.M. Hospital Ship “Salta”. This vessel has since been sunk by enemy action.Arriving at Marseilles on April 5th the unit disembarked, and after a few days waiting for orders, proceeded by rail and arrived at Rouen on April 13th 1916; and the hospital was opened for the reception of patients on April 29th 1916. The 1st A.G. H. has thus been receiving patients in France for considerably over two years. The patients received have been from all ranks (except officers) of the British Armies in France viz : English, Irish, Scotch. Welsh, South African, Canadian, New Zealand, and our own Australian soldiers, etc. No distinction are made. Recently some U.S.A. soldiers of the American Expeditionary Force have also been received. All the patients are treated equally conscientiously and well, and it is a privilege, an honour and a pleasure to be able to do anything to help them in the great cause in which we are all engaged.Following the cessation of hostilities on Nov. 11, the hospital ceased to receive patients in France on Nov. 30 1918 preparatory to its transfer to reopen at Sutton Veney near Warminster, England.The 1st A. G. H. is now in the fifth year of its Active Service and there are very few of the original members amongst its personnel at present. Many changes have taken place owing to the original members and many of their successors having been transferred to other A. A. M. C. units. Several have gone home. Some have been invalided to Australia, and some have “Gone west”.J. A. D.

The Jackass, Christmas 1918

Recent History

The Heliopolis Palace Hotel is today called the Ittihadiya Presidential Palace.

In 1958 it was purchased from its original owners by the state which who considered converting it into a municipality of Cairo administration building. The plans fell through as the political leadership under President Gamal Abdel-Nasser preferred a more fitting location on the banks of the Nile in front of the Egyptian Museum.

In 1972 a new function was assigned to the Heliopolis Palace, becoming the headquarters of the Arab United Republic which united Egypt, Syria and Libya. And hence the name Ittihadiya (Arabic translation for Union) and Uruba Palace (Arabic translation for Arabism).

Ever since, Ittihadiya has been the office of all the presidents of Egypt, a function that transformed the Heliopolis Palace into a presidential palace.

No comments:

Post a Comment